This post first appeared on the Port Washington Patch.

In a recent discussion of the Edward Snowden Affair with family members, two basic attitudes toward the government’s selective spying on U.S. citizens emerged:

The Innocence Argument “I have nothing to hide, so I don’t care what the federal government wants to know about me.”

The Privacy Argument “The government should keep out of my personal life.”

Both viewpoints have valid arguments supporting them, and sensible advocates. But there is a third attitude.

The Fallibility Argument “The federal government’s systems can’t (yet) be trusted to avoid false positives and expeditiously remediate errors.”

Blogger Jeff Jonas noted that:

The underlying problem is that the information on these watch lists typically have low fidelity (i.e., limited data points like only name and date of birth). If you want to see an example of a government watch list check out the Office of Foreign Asset Control’s Specially Designated Nationals Watch List. You will find this frequently contains only a name, date of birth and place of birth.

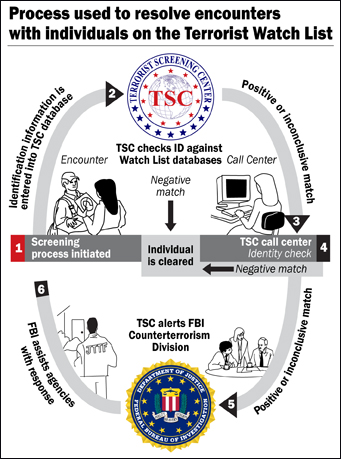

Consider the case of Sean Kelly, who somehow found himself on the TSA watch list a few years ago. The TSA has since rolled out “Secure Flight,” but even a cursory glance at the system’s complexity and scale — 2 million passengers daily moving through 450 ports across the U.S. – instills a healthy skepticism that false positives can be avoided.

As the public debate over Snowden and PRISM rages on, consider the ways in which a citizen’s name could appear in a possible watch list data set:

- A friend’s email list was corrupted by a spambot and you were sent an email from a person on the watch list

- Your name was adjacent to a person on the watch list and a DHS analyst accidentally selected your record

- Your name was misspelled in the government records• You used to live at an address once occupied by a person on the list• You have a common name

- The software performing compiling the lists and/or extracting candidate metadata contains undetected bugs that have compromised data integrity (See GlitchReporter.com for examples)

- A disgruntled insider within the government could scramble the underlying data, a problem which could remain undetected for months or even years

- Recourse software, designed to give citizens an opportunity to appeal false positive classifications when disclosed, is inadequately tested

- Across-the-board government cutbacks have affected program staffing understaffed and software supporting citizen recourse systems are no longer well maintained

Recently NPR’s This American Life chronicled the sequence of bureaucratic bumbling, auto-responders and inadequate supervision and training that apparently led to the beheading of an Iraqi national who had worked for a U.S. contractor.

Imagine that your name or account number appeared on a search of the metadata collected as part of the Prism program. Assuming you had recourse, consider the sort of correspondence needed to extricate yourself from the web of trouble in which you find yourself entangled. It is all too easy to imagine receiving messages from government agencies worded thusly:

Kindly be informed that we checked your case and found that it is in processing pending verifying your employment documents. Once it is completed we will move forward with your case. Your patience does assist us in accelerating the process.

The Orwellian message was repeated often, even after the Iraqi national had reportedly provided the verifications requested.

The Fallibility Argument isn’t a Paranoia Argument. It merely recognizes the limitations of systems created on this scale and run by a very large organization with unclear oversight. It can be assumed that some of the deficiencies have been corrected, but the Department of Justice Inspector General report on issues at the FBI’s Terrorist Watch Center is worth reading. After all, recent revelations about Prism indicate that there are “117,675 active surveillance targets.”

If a two year old toddler could end up on a list, it’s conceivable that the FBI’s data is telling them that one of those targets knows you.